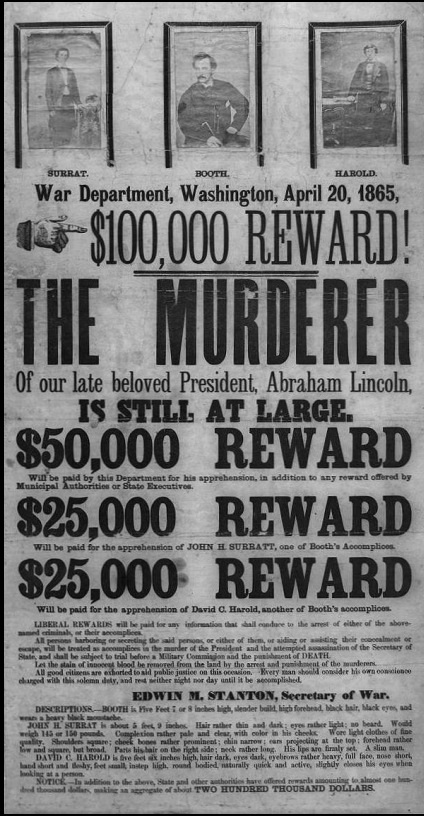

The original photographic wanted poster

Before there were wanted posters in the Old West—those standard props in Hollywood Westerns, featuring mug shots of glowering, greasy-haired murderers and train robbers, bushwhackers and cattle rustlers, card cheats, horse thieves, and all manner of other evildoers—there were wanted posters offering rewards for information leading to the arrest of the conspirators in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln in 1865.

I’ve seen these broadsides with and without photographs. In America, at least, the version with photos is believed to be the first to feature real images of wanted men. Small surprise that the newest technology would be employed: it was in the service of a nationwide manhunt for the murderers of the president, after all. (I’ve seen an earlier poster from England with a skillful engraving of a fugitive thief, which was no doubt rare and would have been costly, but it happened that the crook ripped off the sister of the engraver, so he volunteered his artistic talents to the pursuit.) However, the photographs are not printed on the paper but are albumin prints affixed to the poster, of which a very limited number of copies were made: the technology to print photos on paper for wider circulation (as in books and newspapers) had not yet been invented.

Wanted in the West

The great Marshall Trimball, official historian of the state of Arizona, True West magazine columnist, prolific author, and an authority on the Old West whom I’ve consulted in the past, was asked by a True West reader when photos were first used on wanted posters.

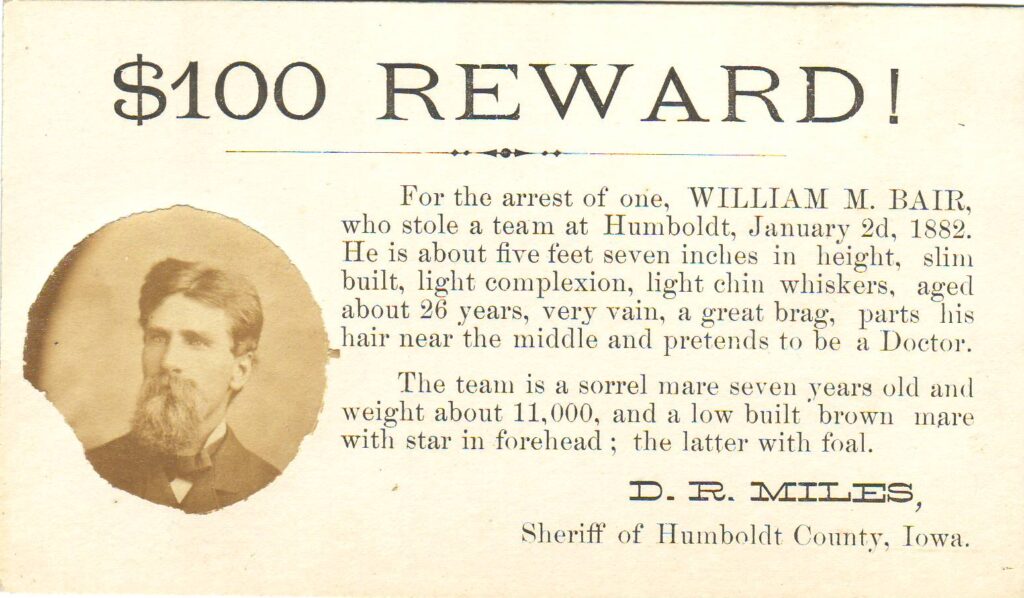

“In the classic era of the Old West—1870s and 1880s—most reward posters were just handbills or postcards sent to law enforcement officials with printed descriptions of the wanted men. No photos . . . ,” Trimble replied.

“Authorities rarely placed wanted posters in public places. A reward or wanted notice would occasionally be printed in a newspaper, but for the most part, they were not intended for general consumption.”

—Marshall Trimball

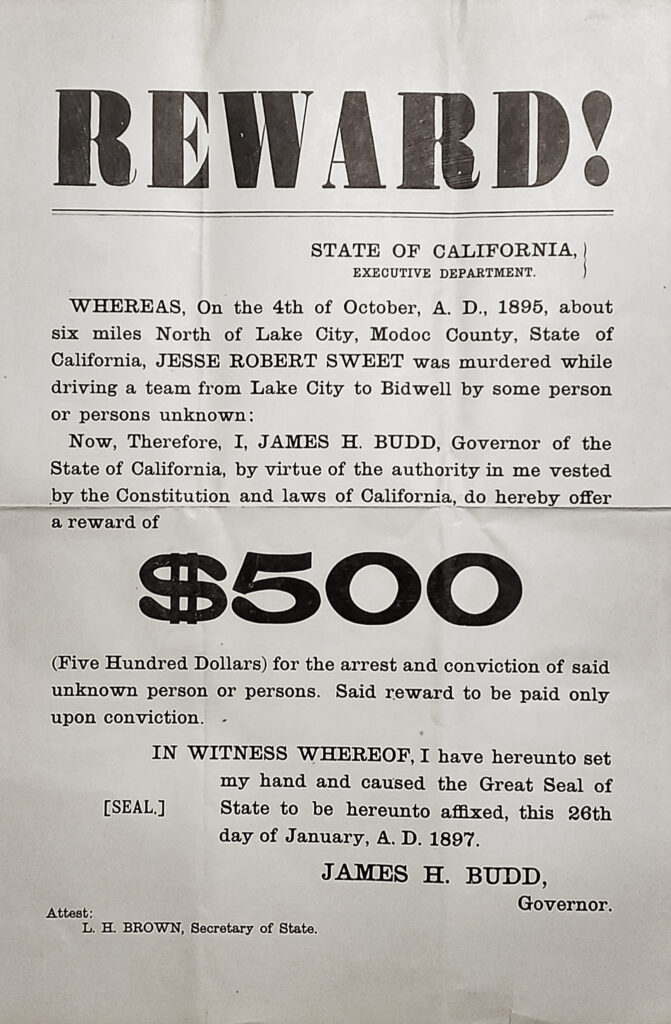

He pointed out that it wasn’t until the late 1890s or early 1900s that entirely printed handbills and wanted posters featuring images of outlaws began to appear as printing technology evolved: “For example, the Pinkertons put out several posters of the members of the Wild Bunch, complete with pictures.”

Prior to that, “some lawmen carried photos made of criminals when they were in prison,” Trimball observed. “The backs of these mug shots featured descriptions that included height, weight, hair and eye color, scars and identifying marks. But these were put together by hand, and the photos were originals, not prints. I’ve seen these saddlebag circulars, and they are amazing. You can see the seeds of the later wanted posters that we think of when we watch Western movies.”1

I’ve seen the Wild Bunch posters that Trimble mentioned, issued by the Pinkerton National Detective Agency: they are double-sided “circulars” (the Pinkerton agency’s own term) loaded with information on Butch Cassidy, Harry Longbaugh (the Sundance Kid), and other members of the gang, and they all seem to date from 1904—relatively late. Also, they don’t look like the kind of things that would have been put up on a wall or lamppost, and in fact Trimble notes: “Authorities rarely placed wanted posters in public places. A reward or wanted notice would occasionally be printed in a newspaper, but for the most part, they were not intended for general consumption.”2

So that’s two myths exploded: wanted posters in the Old West weren’t put up on Main Street in Big Bug, Arizona Territory (which used to be an actual place but is now a ghost town), and they didn’t feature the likenesses of bad guys, either drawn or photographed—at any rate, not prior to the turn of the twentieth century.

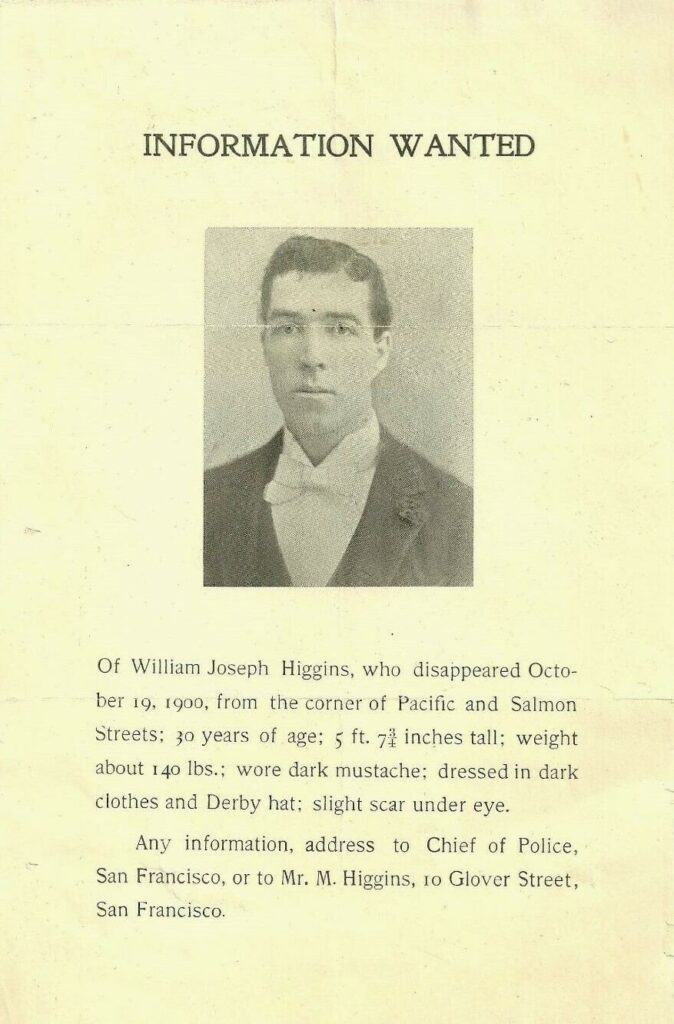

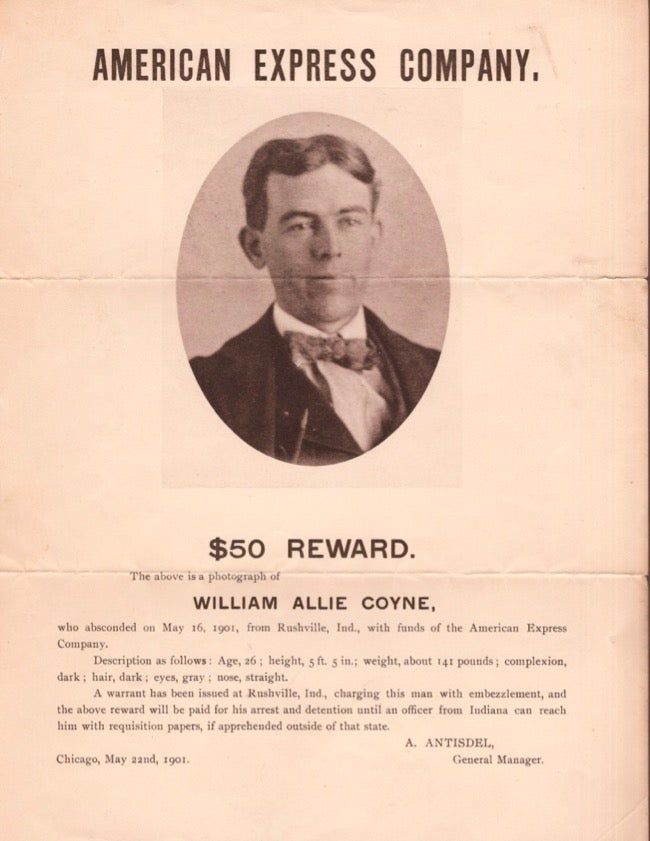

Early posters with printed photos

Since the Butch Cassidy/Sundance Kid/Wild Bunch posters of 1904 are often cited as among the earliest wanted posters with printed-on photos, I started looking for earlier ones from west of the Mississippi. The oldest I’ve found so far dates to 1900, but I’m certain that there are earlier ones. Some examples follow. They are often found on book dealers’ websites and on eBay, as are earlier ones with applied photos. The ones on this page that are from booksellers were still available at the time of this writing.

Notes

- Marshal Trimball, “When Were Photos First Put on Wanted Posters?,” True West, June 10, 2013, accessed August 2, 2025, https://truewestmagazine.com/article/when-were-photos-first-put-on-wanted-posters/.

- Trimball, “When Were Photos First Put on Wanted Posters?”

COLLECT THIS EXPERIENCE! While researching the above story, I came across a great website called I Review Westerns. These are thoughtful, intelligent, earthy, no-holds-barred assessments of Westerns—films and literary works—by someone who is clearly devoted to the genre. You may not agree with all the reviews, but they are an awful lot of fun to read. I encourage you to visit IReviewWesterns.com.