This marks the start of a new feature on Northwest Collector: cool finds that other collectors missed.

I love getting interesting stuff cheap—especially when there are no competing bids at auction. It means I spotted something others didn’t. How much fun is that?

My fellow Old West collectors may appreciate this recent purchase. . .

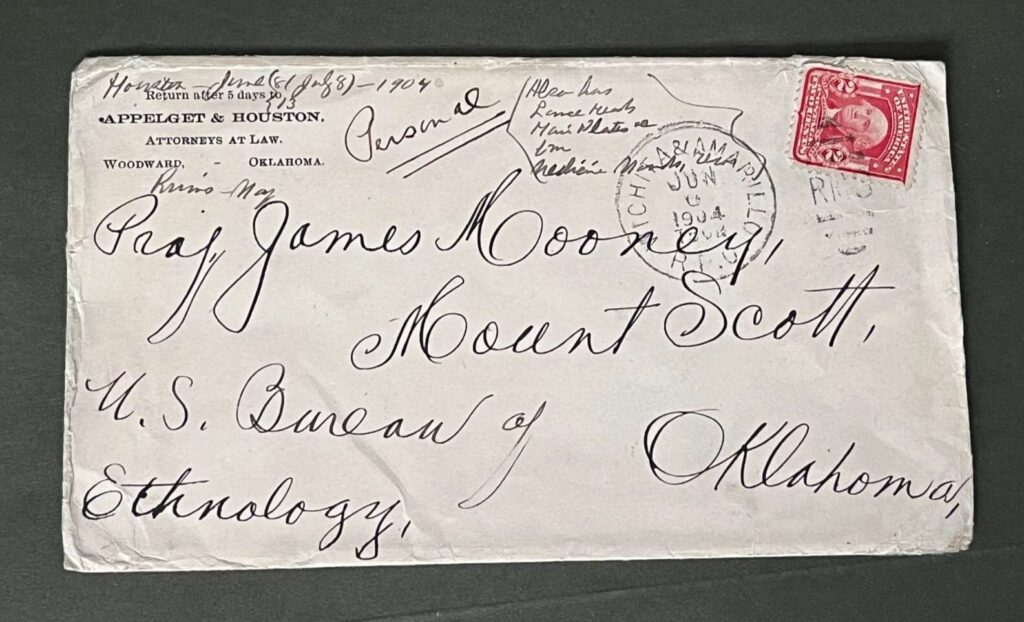

Envelope addressed to James Mooney

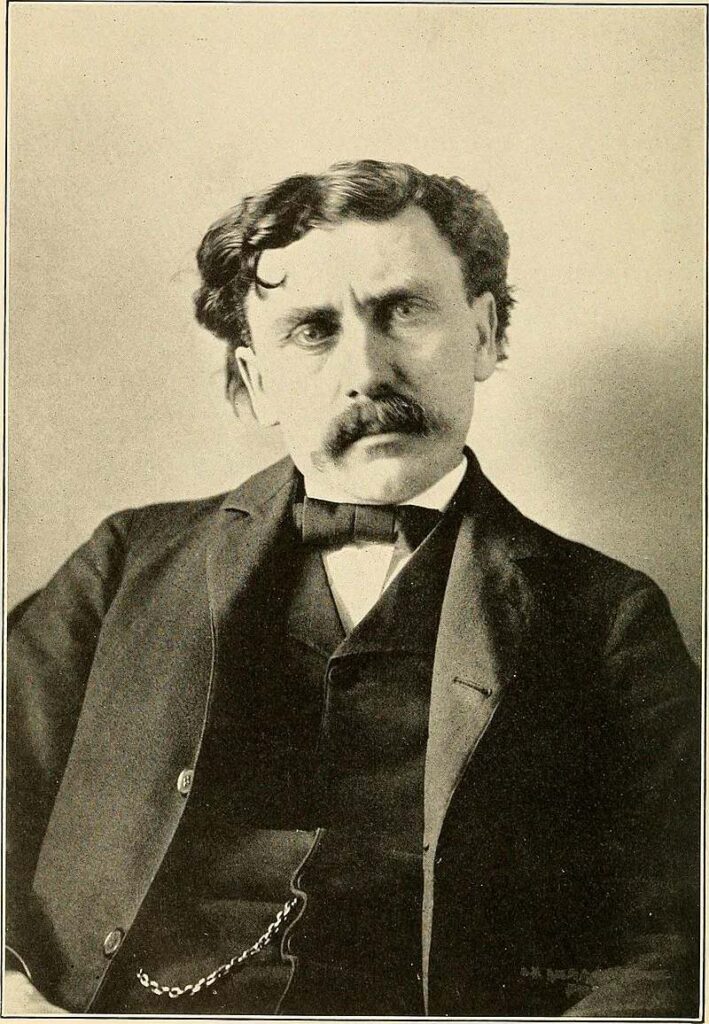

James Mooney (1861–1921) was a self-taught ethnographer and authority on the American Indian; he wrote important works on the Cherokee, Kiowa, and Cheyenne. In the 1880s he joined the Bureau of Ethnology (which would be absorbed by the Smithsonian) and investigated the Wounded Knee “Outbreak of 1890” at the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. He published his research on the Ghost Dance (U.S. Army suppression of which led to the assassination of Sitting Bull, conflict with the Lakota, and the subsequent massacre) in bureau’s 14th annual report in 1896 (a popular issue and somewhat pricy volume, presumably in large part because of extensive Mooney article, but you can download a pdf from the Smithsonian website). Mooney was also an accomplished photographer, and original prints of his Indian images are rare and expensive. Almost all of his letters seem to be at the Smithsonian and therefore are virtually unobtainable.

No surprise, then, that this cover, sent in 1904, contained no letter, but it’s still an item with a story or two.

For one thing, it’s written to Mooney in Mount Scott, Oklahoma (i.e., Oklahoma Territory, which, with Indian Territory, would become the state of Oklahoma in 1907). Mount Scott, named for General Winfield Scott, is a peak in the Wichita range and located in the what was then the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache reservation. Mooney was obviously doing fieldwork.

There are also a few barely legible notations, one of which says “Also has Lance Heads, Hair Plates . . . Medicine Masks . . .” Apparently the writer had artifacts to show Mooney or sell to him.

So who was the writer? Here’s where it gets really interesting.

The return address is for Appelget & Houston, Attorneys at Law, of Woodward, Oklahoma, I was unable to find out much about law office partner Anthony Appelget apart from the fact that he and his family arrived in Woodward from Sheridan, Wyoming, in 1900.

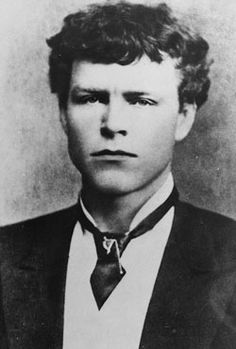

Houston is another story. It turns out that the other partner in the firm was Temple Lea Houston (1860–1905), youngest child of Texas legend Sam Houston. A born adventurer with an intellectual bent and a bit of an iconoclast with an affinity for the Indians, Temple Lea Houston served in the Texas senate from 1885 to 1889. According to Texas Tech University archivist Hugh Allen Anderson, “although flamboyant and sometimes eccentric in dress and appearance, Houston won a reputation as a brilliant trial lawyer and a gifted speaker, whose oratory was laced with allusions to the Bible and classical literature. He was a dead shot and often carried a pearl-handled pistol . . .”1 On one notable occasion, writes True West magazine features editor Mark Boardman, Houston “insulted opposing counsel Ed Jennings during an 1895 trial in Woodward . . . Jennings responded in kind. And then the fight moved to a different kind of bar.” At Jack Garvey’s saloon, the animosity boiled over. Ed Jennings and his brother John got into a shoot-out with Houston. Ed was killed. John was hit but survived.

“John Jennings and his other brothers Al and Frank then took the outlaw trail in a six month misadventure,” Boardman adds, concluding: “Bad lawyers. Bad gunfighters. Bad criminals.”2

“Houston was acquitted after acting as his own counsel and pleading self-defense. Twenty witnesses testified that Ed Jennings had drawn first,” writes “hometown” on the website Hometown by Handlebar, in an article that features the best “primary source” documents on Temple Houston that I’ve seen online.3

But the bad blood between Houston and the Jenning family didn’t end there. The following year Ed Jennings’s father, a judge, ran into Temple Houston’s young son on the street when the boy was returning home from school. The judge spat in the younger Houston’s face in response to something the kid said. “[Temple] Houston killed father Judge Jennings in the same saloon where Houston had killed son Ed Jennings . . .” notes hometown. “In 1897 ‘the son of Sam Houston’ pleaded guilty and was fined $300 for killing Judge Jennings in 1896.”4

“Although flamboyant and sometimes eccentric in dress and appearance, Houston won a reputation as a brilliant trial lawyer and a gifted speaker, whose oratory was laced with allusions to the Bible and classical literature. He was a dead shot and often carried a pearl-handled pistol . . .”

Badassness aside, Houston was an inspired courtroom performer and legal advocate. In 1899, Woodward prostitute Minnie Stacey was put on trial for, um, prostitution, but lacked legal representation; the judge asked Houston to take on the case. “He had all of ten minutes to prepare a defense,” writes John Troesser of TexasEscapes.com, a really excellent online magazine devoted to the history of the Lone Star State. “Since everyone in town knew her—or perhaps we should say everyone in town was aware of her reputation—Temple knew that a defense was hopeless. So he attacked men in general for creating women like her and was so forceful in his condemnation that there wasn’t a dry eye in the courtroom—excepting the lawyers.”5

Houston’s defense of Stacey is now known as the “Soiled Dove Plea” or “Plea for a Fallen Woman.”

Obviously, Houston—the subject of the 1980 biography Temple Houston: Lawyer with a Gun by Glen Shirley (University of Oklahoma Press)—was the kind of character that fascinates students of the Old West like your humble correspondent.

Which adds that more spice to this cover: I was able to find a letter by Temple Houston online (priced at $1,500) and—cowabunga!—the handwriting matched perfectly. Purchase price: $19.99 plus tax and shipping. Satisfaction value: priceless.

Notes

1. Hugh Allen Anderson, “Temple Lea Houston: A Legacy of Law and Oratory in Texas,” Texas State Historical Association, 1952, updated October 26, 2019, accessed July 13, 2025, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/houston-temple-lea.

2. Mark Boardman, “Temple Houston,” True West, June 18, 2015, accessed July 13, 2025, https://truewestmagazine.com/article/temple-houston/.

3. hometown, “Temple Houston: Standing in the Shadow of Sam,” Hometown by Handlebar, August 15, 2019, accessed July 16, 2025, https://hometownbyhandlebar.com/p-7219/.

4. hometown, “Temple Houston.”

5. John Troesser, “Temple Lea Houston: Son of Sam,” TexasEscapes.com, October 2002, accessed July 14, 2025, http://www.texasescapes.com/TexasPersonalities/TempleLeaHouston/TempleLeaHouston.htm#google_vignette.