I love auction catalogs: Even if I can’t afford to bid on what I really want—and how many collectors can?—the catalogs make for fun reading.

Catalogs are also a great resource for collectors. Over time, they can give an idea of what’s out there on the market and—if you bother to check the hammer prices afterwards, which I strongly advise—what certain items may fetch. The operative word is “may,” of course; more on that in a moment.

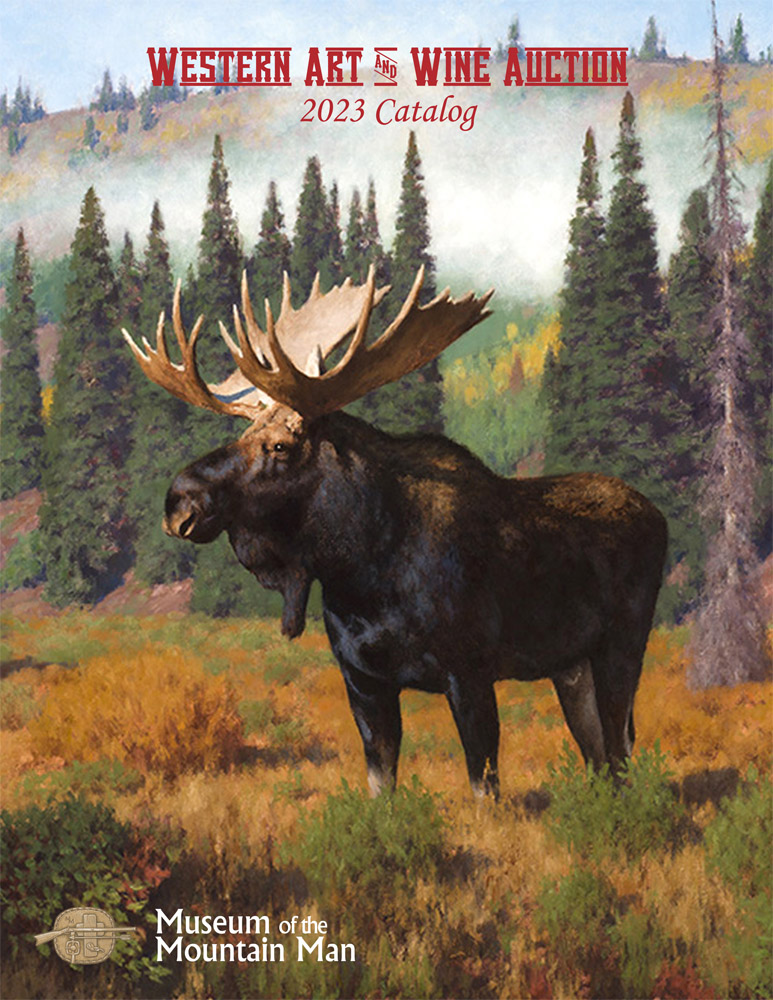

The catalog for the 2023 Western Art and Wine Auction at the Museum of the Mountain Man in Pinedale, WY. The cover art by Tucker Smith (TuckerSmithArt.com), Morning on Ditch Creek, is a signed artist’s proof giclée print on canvas made from one of Smith’s spectacular oil paintings. “All art is donated specifically for the auction, mostly directly by the artists, to be auctioned to benefit the museum collection, and all proceeds go to the museum,” according to Clint Gilchrist, the museum’s executive director. “The cover art is always one of the pieces donated for the auction.” See all the catalogs at https://museumofthemountainman.com/artauction/. The next auction will be on July 11; the catalog will be online on June 1. Catalog cover image used by permission of the Museum of the Mountain Man.

If you collect within a narrow field, you may even see an item come up for auction more than once over a period of a few years. If it’s a rare or one-of-a-kind piece, it can help you to know what it sold for the last time it went on the block.

Lot descriptions are also informative, both for what they contain and what they don’t. A really good auction house with knowledgeable experts—Heritage Auctions in Dallas, say—will publish beautiful catalogs with insightful descriptions that contain valuable details about an item’s uniqueness, provenance, condition, etc. But don’t let that stop you from doing your own research: If you collect Theodore Roosevelt memorabilia, for example, and a letter from Teddy to a Mr. Joe Blow comes up for auction, do your homework and try to find out who Joe Blow actually was, if the auctioneer hasn’t done so already. Special associations often go unnoticed and only add to an item’s worth.

Hard-copy catalogs are relatively inexpensive collectibles in their own right—and well-illustrated ones are as good as any coffee-table book . . .

Here’s an example: Some years ago, a short 1909 Christmas greeting written by legendary 19th-century boxer/Civil War veteran Mike Donovan to a Captain Jack Crawford came up for auction. Donovan’s handwriting wasn’t so legible, and the lot description querulously noted that Donovan referred to Crawford as “the Poet Scant.” “Scant”? I was confused too.

So I Googled “Captain Jack Crawford, Poet Scant.” It turned out he was Captain Jack Crawford, known as the “Poet Scout,” who was a lot more famous than Donovan (at least, outside of pugilistic circles). Both men had been born in Ireland and served in the Union Army, so they obviously had some common bonds. Crawford became a cavalry scout in the Indian Wars and was among the first to arrive at the site of the Little Bighorn fight after Custer’s 7th Cavalry were killed. Crawford was also famous as a frontier poet, hence the moniker: He used to pen his verse at campfires—while his compatriots were drinking, eating beans and farting, one imagines—published several books (pretty avidly collected today) and was active on the public reading circuit. And he was a pal of Buffalo Bill Cody, with whom he later worked the Wild West show circuit.

All of this evaded the writer of the lot description, but it greatly enhanced the note’s value—both to your humble correspondent and the guy who outbid me!

Hard-copy catalogs are also relatively inexpensive collectibles in their own right—and well-illustrated ones are as good as any coffee-table book—in addition to being great reference material and useful as “provenance” if you acquire something that has been auctioned off in the past. Here’s a great 2020 movie poster auction catalog from Heritage Auctions in Dallas. Image courtesy of Heritage Auctions (HA.com).

Anyway . . . bear in mind that while hammer prices may provide an indicator of an item’s fair-market value, nothing’s written in stone. Just as on eBay when two goons get in a bidding war and drive an item’s price ski-high up five days before the end of the auction, people in an online or live auction can get crazy and bid far beyond what they reasonably should. (Figure in the buyer’s premium as well.) So take hammer prices with a few grains of salt.

Conversely, you may get lucky—as I have more than once—and find a great item BURIED in an auction catalog among unrelated items: for example, an uncommon film star autograph hidden among sports memorabilia. Not only will other collectors of that film star miss the autograph (unless they collect sports memorabilia too) but the sports people will probably ignore the film star as well. Then you have the opportunity to nab a great item far below what it would ordinarily sell for.

In a nutshell: Look hard for those hidden gems among the other lots!

A final word . . . I originally wrote a version of this story about 15 years ago. Catalogs, for the obvious reasons of lower cost, speed, and convenience, are nowadays often sent out only as pdfs or links to web pages. Occasionally you can find them online on Google Books. If you don’t want to download and keep the pdfs on file, you may be able to view past sales on an auctioneer’s website.