There’s a learning curve for any novice collector, and it can be expensive—not just because one can overpay for a collectible before knowing enough about rarity or scarcity, or even buy a counterfeit item, but because new collectors tend to buy a lot of stuff on impulse before deciding to specialize.

Kuniteru, “The Steamship Carrying the Chief Priest of Higashi Honganji Temple in Kyoto Is Welcomed to the Port of Hakodate in the Northern Island of Hokkaido,” 1870, oban triptych (29″ X 141/2“). (The black boat at the right edge of the center sheet has the American Consul on board. The American consul. Mr. Rice, came to Hakodate in 1857.) Courtesy of Peter Gilder, Arts and Designs of Japan.

Having collected 19th-century and early 20th-century Japanese woodblock prints for a number of years and seen the prices climb steadily on dealers’ websites, my advice from the get-go: Read up on Japanese prints online, view the wide range of themes and the works of individual artists, and try to collect prudently. If you plan to collect prints seriously—that is, not just pick up a samurai image as a gift for a martial artist friend, or a nostalgic landscape of a place you may have visited on a trip to Japan—I believe it’s better to collect narrowly and then expand your range than to buy widely at first and then focus. At the very least, you’ll potentially save yourself a lot of money.

“It’s best to store prints in acid free folders in acid free boxes. No exposure to light.”—Peter Gilder

I also strongly believe you should learn something about preserving the prints, information on which I’ve found to be pretty elusive on the internet. For example, I think it’s a bad idea to buy matted and framed prints, as you won’t know what the borders look like. Furthermore, you need to be careful about framing and displaying prints, as Japanese printmakers used “fugitive” ink that can fade over time when exposed to light, even if framed under UV-light-resistant museum-quality glass. (I read somewhere that museums that display framed Japanese prints do so for only two or three months at a time, under low- or non-UV-light conditions, then rotate them out.) Granted, it may take years for the ink of a framed print to fade noticeably in ambient (indirect) light, but do you really want that when your print’s colors have already remained vibrant for 125 years or more?

Another word of advice: Try to have an idea of what your print should look like. That won’t be possible for all prints, as there are many thousands of images, but you may find that the colors of the print you are considering are not as nice as another example you have found online—or you may discover, as I have, that that the oban-size (roughly 10″ x 15″) print that you bought is actually only one panel of a two- or three-part print, which the seller failed to mention.

And needless to say, just as the real estate mantra is “Location, location, location!” in collecting it’s “Condition, condition, condition!”

Kuniyoshi, “Katsuenra Genshoshichi Protecting Himself from the Government Arrows with a Tiger [Leopard] Pelt,” from the series “108 Heroes of the Popular Suikoden, c. 1827–30,” published by Kagaya Kichibei, oban-size (101/8” x 145/8“). Courtesy of Peter Gilder, Arts and Designs of Japan.

When I have the itch to buy a new print, I have my main go-to people, and at the top of my list is Peter Gilder of Arts and Designs of Japan, a San Francisco–based specialist in prints from the 18th to the 20th centuries. Not only are Peter’s offerings invariably in excellent condition—something a collector really has to watch for—but they are very reasonably priced, and he sends out an email with new offering on the first day of every month, which is a huge convenience.

A criminal lawyer for two years, Peter quit to live in Japan for several years, becoming an amateur master second-degree go player. On returning to California, he started a Japanese print business, which he’s been running for 47 years. He is an associate (i.e., overseas) member of the Ukiyo-e Dealers Association of Japan.

I asked Peter a number of questions intended to provide new and prospective collectors of Japanese woodblock prints with some basic information on these beautiful works of art and hopefully save them some aggravation and money in the process.

Q: How widely collected are Japanese prints, and have they become more popular in recent years?

Peter Gilder: Japanese prints are collected wherever there are human beings. There are always new collectors appearing and old ones disappearing. I would say they have become less popular recently partly because of the rise in interest in other Asian art particularly Chinese, and with the much greater monetary abilities of Chinese collectors. Sotheby’s New York ended their Japanese department in the last 10 years, after more than 100 years of auctioning Japanese prints.

Q: People often think “ukiyo–e” is synonymous with “Japanese woodblock prints,” but that’s incorrect. Can you explain?

PG: “Ukiyoe” simply means pictures of the floating world, a kind of Buddhist concept of the transitoriness of life. It was taken to mean images of the pleasures of life, whether courtesans of the pleasure quarters, a beautiful landscape, etc. So “ukiyoe” would embrace woodblock prints, paintings, lacquer, ceramics, and other art forms.

Q: Is it true that 19th-century Japanese didn’t consider block prints to have much artistic merit?

PG: Japanese prints were essentially the art form for the emerging middle class: merchants, who had money but little status in the societal hierarchy. That’s why such a large part of the art is devoted to the theater and the pleasure quarters. Also, landscapes and warriors, myths, ghosts, etc. Among this group, Japanese prints were important. No doubt, they thought that the art form was less important than the official schools of painting that the nobles might favor.

Q: When did Japanese prints become popular in the West?

PG: Japanese prints have been filtering west since the late 1700s through Deshima, in Nagasaki Harbor, a Dutch outpost at that time. After Japan reopened, in the 1860s, the prints became popular through visitors from other Western countries. I once had an album of prints that were collected by one of the sailors on Commodore Perry’s ship [in the early 1850s]. The great influx, though, started in the late 1800s and has continued since.

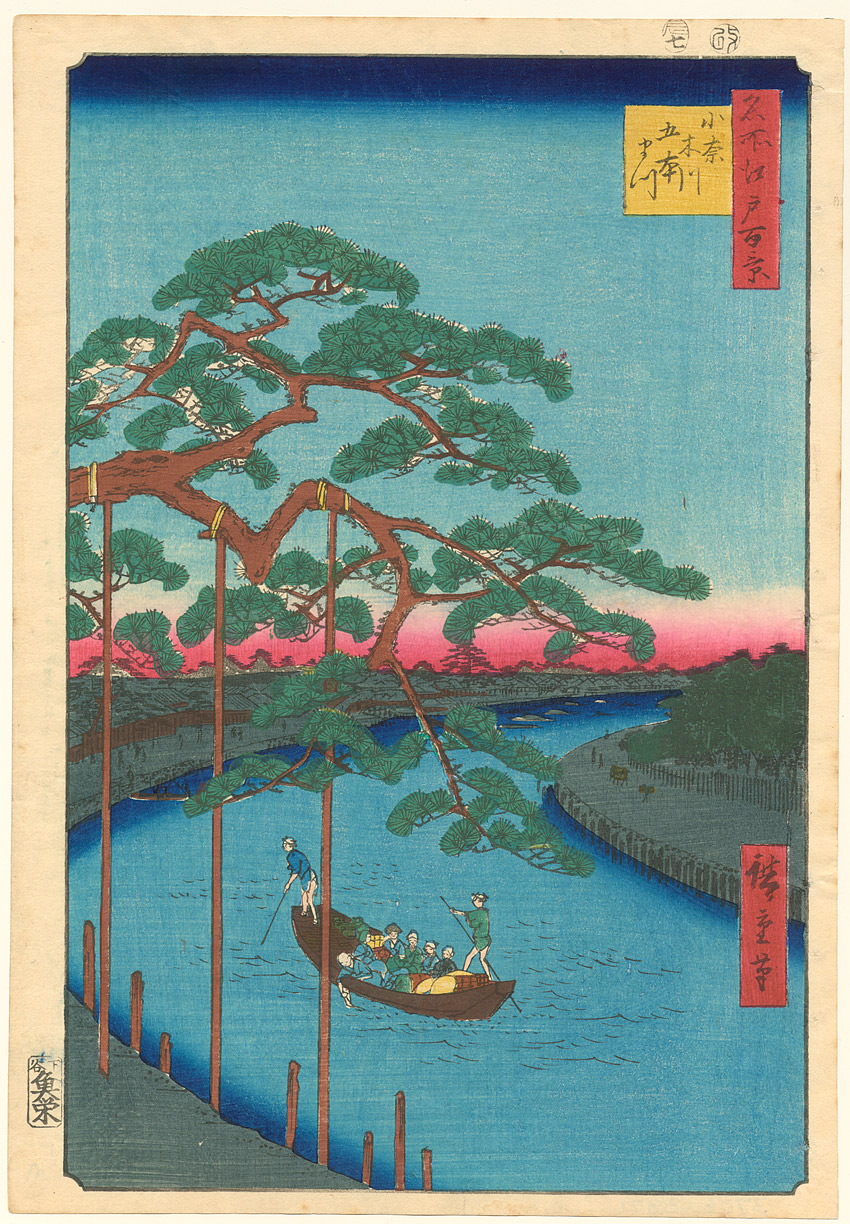

Hiroshige, ”Onagigawa Gohonmatsu [Five Pines, Onagi Canal],” from the series ”100 Famous Views of Edo,” July 1856, published by Uoei, oban-size (93/4” x 141/4“). Courtesy of Peter Gilder, Arts and Designs of Japan.

Q: Where were prints traditionally made, and how many people were involved in the process?

PG: Woodblock prints were produced throughout Japan, but the great majority were done in Edo (the old name for Tokyo). Osaka was number two, probably Kyoto number three. Nobody knows exactly how many people were involved in the production of any particular design. But of course there was the artist (or artists, if more than one collaborated) who produced the finished sketch. Then the carvers who incised the design into wood blocks. More experienced carvers did the faces and hands; less experienced carvers did the rest. After that, there were the printers who mixed up the dyes and applied them to the blocks. Finally, there was the publisher who hired and paid them all and presumably supervised the whole process, then sold the prints in his shop.

Q: What distinguishes Osaka prints from others?

PG: There was a certain amount of cross fertilization between Osaka and Edo prints. A number of artists, like Toyokuni I, went back and forth and worked in both places. The prints were fairly similar until the late 1840s when Osaka prints changed to a mostly “chuban” (half-size) format and were lavishly printed. Maybe they weren’t as affected in Osaka by the sumptuary laws that forbade such things. They were also almost exclusively theatrical in Osaka.

Q: Is it true that prints were often used to illustrate sensational crimes and events—like 19th-century tabloid journalism? Is there a tangible connection between traditional block prints and modern manga?

PG: Prints illustrating sensational events were common in the Meiji period and must have been popular. No doubt, there is a strong connection to manga. I’m sure many manga artists are very familiar with the older prints.

Q: What are the most popular themes and artists among, say, American collectors?

PG: I don’t think there are really any significant differences between collectors geographically anymore.

Q: What determines the prices of prints? What’s your advice on the acceptable “collectible condition” or prints?

PG: The market is of course the final determinant of print value. But I think each dealer should have a certain spectrum of values in mind when they assess particular print.

There are three areas to look at when determining value:

- Identification. Where does this particular print reside in the entire field? For example, if it is something like Hokusai’s “Great Wave,” we know immediately where to place it. For other less well-known items, one has to make a determination, based on artist and subjective estimate of its beauty.

- Impression. How early in the printing process is it? How elaborate are the printing techniques and how special the inks and paper?

- Condition. That means everything that has happened to this particular piece of paper since that day it was printed: wormage, stains, trimming, foxing, etc.

Yoshitoshi, “Osen and Otoku on the Veranda of the Isegan Restaurant at Shibaguchi,” from the series “Kaito Kaiseki Beppin Kurabe [Comparison of Specialties at Restaurants in the Imperial Capital,” April 2, 1878, published by Kobayashi Testujiro, oban-size (91/8” x 137/8“). Courtesy of Peter Gilder, Arts and Designs of Japan.

Q: How do you advise storing or displaying Japanese prints? Is it all right to frame them? (My understanding is that real collectors don’t frame their prints, even under Tru Vue Museum Glass—not just because of the “fugitive” aspect of the ink in traditional block printing, even under low-light conditions, but because of the tactile experience of actually handling the prints. Is this true?)

PG: It’s best to store prints in acid free folders in acid free boxes. No exposure to light. Handling prints is a tricky area as touching the paper with fingers is likely to transfer skin oils to the paper. Best to minimize touching and exposure to light.

Peter Gilder’s website is www.artsanddesignsjapan.com. Sign up for his monthly list, which he usually sends out on the first.